To express joy on a festive Jewish holiday, it is traditional to wear something new. Last week, for a Passover seder at her parents' home in Borough Park, Brooklyn, Suzy Berkowitz, 50, upheld tradition from head to toe. Exemplifying the Diana Vreeland dictum that elegance is restraint, she wore new Gucci pumps and a new Armani suit, hemmed discreetly just below the knee. She also wore a custom-made Kosher wig bought for the occasion.

Like many other Orthodox women who follow Halakha, Jewish law, Mrs. Berkowitz has worn a Sheitel since her wedding day. Women's hair exudes sensual energy, the Talmud teaches, and covering it insures a married Jewish woman's modesty. But the Talmud also obliges a wife to care for her appearance, so though a hat or scarf will do, many Orthodox women favor Kosher wigs, the more natural looking the better.

In fact, it was impossible to tell that Mrs. Berkowitz's rich, auburn hair -- bobbed chin length with soft bangs brushed off her face -- was actually a wig. Stylish Orthodox women like Mrs. Berkowitz eschew synthetic ready-made wigs for custom ones of human hair that closely approximate their own tresses. And much attention is paid, from purchase to the cut and style (new high-end wigs come straight and uncut).

"We talk about wigs the way women who don't wear them talk about their hair," said Liba Noe, 45, of Borough Park, who with her husband owns Eshel Jewelry Manufacturing in Manhattan and who owns a Claire, called by its aficionados the Rolls-Royce of Orthodox wigs. "When women get together at a wedding or a party they ask, 'Where did you get your shoes, dress and wig?' They even ask, 'Who did it?' "

For Passover, Suzy Berkowitz chose a $2,000 Olga, made by Olga Berman, a Hungarian wig maker in Bensonhurst (Mrs. Berkowitz also owns a Claire and an equally high status Ralph). For that critical cut and style, she turned to Mark Garrison, whose Madison Avenue salon serves dozens of Orthodox clients who pay at least $600 to have their wigs transformed.

"Orthodox women want something contemporary and realistic, and don't want a wig to look like what it is," said Mr. Garrison as he began the slow, tedious process -- three to four hours -- required to shampoo, cut and style a wig. "It's a challenge. You can't rely on next time. There is no next time."

Most swank stylists, including Frederic Fekkai, John Barrett, Oribe, John Sahag and Oscar Blandi, do wigs for Orthodox women. They aim to make them modest but not matronly and definitely not wiggy, the word Orthodox women use to describe the heavy appearance of Kosher wigs.

Taking the idea of verisimilitude further, Mr. Fekkai suggested: "An Orthodox woman should have several wigs. A real haircut grows out at different lengths. You need more than one wig at different lengths."

Given the code of modesty that Orthodox women abide by, including clothes that must cover the knees, elbows and collar bone, is it a contradiction to wear a wig, especially a stylish one?

"When the practice of wearing a wig first emerged, there was quite a protest," said Rabbi Rafael Grossman, the president of the Rabbinical Council of America, the world's largest body of Orthodox rabbis. "There are those authorities who strongly object. A wig would seem to contradict the basic principal of avoiding incitement. But my personal view is that it is acceptable because the rudiments of Halakha only require women not to expose their hair, though a woman should avoid wearing a wig that could appear to be sensual."

Rabbi Avi Weiss, of the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale in the Bronx, agreed. "I would distinguish between being stylish and being immodest," he said. "Jewish law is not monolithic. There can be two views, and they can be both opposite and correct."

Wearing a Kosher wig is a fairly modern Jewish practice. Before the 19th century, proper Jewish women covered their hair with shawls or veils. In feudal times, some women actually shaved their heads to detract from their appearance and thwart rapacious landlords who had the right to claim a bride's virginity before the groom did. Today, some women who are Hasidic, an Orthodox sect, still shave their heads as an added measure of propriety. But by and large, women either pin their hair up or cut it short and wear a wig.

Many young Orthodox brides insist on wigs that match their hair in style, texture and color, which also helps ease the jitters when a newlywed first dons a wig. "I want my wig to look exactly like my hair," said Elky Stern, 22 and a student at Touro College in Brooklyn, whose long blond hair will be covered when she gets married in June. "At college, everyone who is engaged discusses wigs. Even the guys talk about it because they know the girls are nervous."

Before she was married two years ago, Rifka Locker, 20, a fourth-grade teacher from Lakewood, N.J., had Mr. Garrison style her straight, red hair. He cut it above her shoulders, angled it around her face, and layered the top in a style that became the prototype for her straight, red wig. (Orthodox rabbis frown on male stylists working on a woman's real hair once she is married). Putting on the wig the morning after her wedding, Mrs. Locker remembered: "I was confident wearing it. No one could even tell I got married."

Mrs. Locker bought her two wigs -- custom-made for special occasions, ready-made for everyday -- at Claire's Accuhair in Midwood, Brooklyn.

Claire Grunewald, who is Zsa Zsa Gabor-like with her false eyelashes, rhinestone-rimmed glasses and strawberry blond bob with honey highlights, is an expert sheitel macher, or wig maker. A Holocaust survivor from Hungary, she spent three years after the war in a displaced people's camp, where she was an apprentice to a German wig maker. Mrs. Grunewald immigrated to the United States in 1949, at age 17, and has devoted most of her 65 years to Orthodox women.

"I had the most beautiful strawberry blond hair and didn't want it covered when I got married, but my religion dictated it," she said. "To make matters worse, no one could style my sheitel the way I liked it. At 19, it made me look 35. So I started making my own wigs. Then I had a dream to manufacture a beautiful wig for the Jewish community. I had a dream that when you walked down a street, you wouldn't be able to say, This young woman is wearing a wig."

The Jewish women who make up most of Claire's affluent clientele travel from as far away as California and Israel for the wigs made on the premises of her family-run shop, complete with private fitting rooms. Of the 15 female workers, many sit at banquet tables, ventilating, or tying, strands of hair into wig foundations. The three male workers, who are not permitted in the salon where women try on wigs, sort unrefined hair, primarily imported from Eastern Europe, where a woman's braid sells for enough to feed a family for a month, Mrs. Grunewald said.

Six to eight braids per wig are woven into a lightweight, durable silk or lace-fitted cap. If styled, the process can take 40 to 60 hours. The cost is $1,700 for a Contessa, the ready-made style, and up to $4,000 for a custom design, depending on length and quality of hair. The expense, by tradition, falls on the bridegroom's parents.

"A Claire wig is a designer thing," said Chaya Nachsoni, the executive secretary of the company and one of Mrs. Grunewald's three daughters working at the shop. "People say to me, 'Oh, a Claire,' the wig everyone wants but no one can afford. It's the Rolls-Royce of wigs."

The status attached to a Claire wig is matched only by a Ralph, as in Raffaele Mollica, who works out of an atelier at 75th Street and York Avenue in Manhattan, where the floor is strewn with strands of hair and the walls lined with every variety of wig imaginable. There are long, dark Cher tresses, short, gray Geraldine Ferrara coifs, curly red Chelsea Clinton locks. Mr. Mollica, a native of Sicily, says he has had hundreds of Orthodox customers over the years, paying $2,700 to $3,500 for a wig that may take up to a year to make. Ralph devotees say it is well worth the wait.

Mr. Mollica got his start making wigs for Vidal Sassoon, who led the hair revolution of the 1960's, from set-and-tease to loose, flowing styles. Mr. Mollica has adapted his mentor's vision to wigs.

"He makes a wig cap which is white like my scalp," said Elisa Mermelstein, 29, a customer from Kew Gardens, Queens. "Also, the hair is thin, which prevents the wig from looking bulky. A white scalp and flat hair. Those are Ralph's trademarks. They make for a natural-looking wig."

With all the attention devoted to wigs, is there ever an opportunity for women to let down their real hair?

"Whatever the Torah prohibits the Torah permits," said Rabbi Mayer Fund, founder of the Flatbush Minyona, a synagogue in a largely Orthodox section of Brooklyn.

Since swimming is segregated by sex in Orthodox communities, women swim bareheaded, allowing their hair, which darkens from lack of sunlight, to have a fleeting chance to highlight naturally. And when Orthodox women are at home, where many wig-wearers don only a scarf lest an unexpected visitor appears, they will uncover their hair when ready for bed.

"You're keeping your hair for your husband," Mrs. Mermelstein explained. "He's the one who gets to see it."

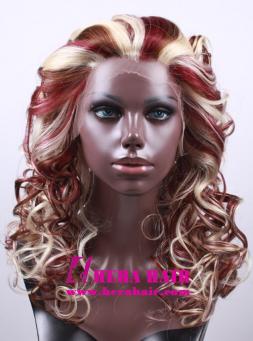

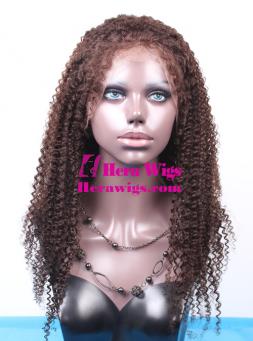

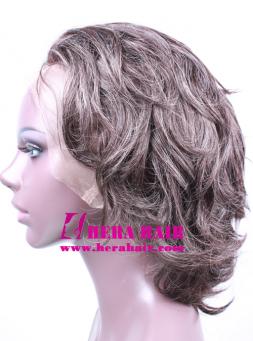

Hera is the best sheitel maker in China and Hera only use the top quality European hair to make sheitels with Kosher Certification and the most important that you afford the premium Kosher wigs. If you have any requirement, please feel free to contact us by sales@herahair.com .