Searching for the Perfect Jewish Women Wig

To pilfer a phrase from the late Nora Ephron, I feel bad about my sheitel, the matron’s wig I wear for religious reasons.

The one I’ve been wearing for the past four years is part of the problem: Not only is the cut dated, the hair has gotten so stiff and dry that it could probably be mowed into toothbrush bristles. As my calendar has grown crowded with upcoming family events, I’ve started to search for a replacement, though I realize it’s not likely to make me feel much better.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not conflicted about head covering. I like looking Orthodox; if I were a man, I’d probably sport a full beard, peyes, and a black hat. What I don’t like is the trend toward hyper-natural and hyper-expensive “I can’t believe it’s a sheitel” wigs. And yet, I’m too vain to resign myself to a headscarf or a hat. So, I search.

This is how my search goes. I enter a place where sheitels are sold near my home outside Jerusalem. That could be a swanky wig parlor, or a neighborhood social hall, or the back room off the seller’s kitchen. No matter what the setting, the routine is the same. The stylist greets me and guesses my color. No Sunflower Blondes or Leather Blacks; sheitel color is classified by number—ranging from 1 for the darkest shades to 33 for the hardest to find color, red. I’m a 12, plain brown. From the stock room, the seller/stylist brings out “something,” which means a mop of glossy strands, uncut and unstyled.

“Human hair. All European,” she purrs, her voice taking on the tones a Tiffany employee might use when describing a five-carat emerald.

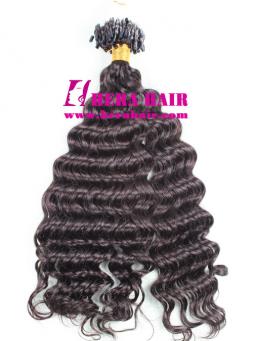

“Human” means the wig has been fashioned from the ponytail of somebody’s daughter or sister or mother. “European,” in the unabashedly racist world of sheitels, is the best hair, followed by Russian, Brazilian and, at the very bottom, Chinese, which is too straight and requires extensive chemical treatments to achieve the desired soft waves.

“Fifteen-hundred dollars, a bargain! Try it on,” she urges.

I try it on and smirk at my image in the mirror.

“Morticia Addams on a bad day,” I say.

The Israeli stylist doesn’t smile; The Addams Family doesn’t resonate with television-avoidant Israeli Haredim. She just scurries back to the stockroom to find another model while I slink out the door so I can run home to gulp down some Advil to fend off the migraine that is coming on.

Like an actor in a bad play, I repeat this scene endlessly—in downtown Geula, where the sheitel shops outnumber the pizza parlors, and in my Orthodox suburb, where sheitel merchants hold one-night-only sales that I religiously attend. And like a bad play, it never ends well.

Maybe I should just quit this search but call me neurotic—I still want a sheitel. That is because in the Haredi world in which I live, a sheitel is like high-heeled shoes: It is a sign that I’m ready to venture out into the world beyond the supermarket.

Yet even after two decades of wearing them, sheitels bother me. Most, though certainly not all, poskim—the arbiters of halakhah, Jewish law—rule that a sheitel is an acceptable form of hair covering. (In Jewish law, married women are required to keep their hair covered—but many women do this by wearing hats, scarves, or sometimes combinations of both.) But the wig concept doesn’t sit well with me. I’m troubled with the implied deception. I mean, isn’t it weird to cover one’s hair by wearing someone else’s?

Maybe my feelings stem from my outsider status. Frum-from-birth women, the born-and-bred Haredim, were raised playing dress-up with Mommy’s sheitels. To them, sheitel wearing feels as natural as having a dozen kids; where I grew up, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, sheitels were as rare as hijabs. In my growing-up years during the 1960s and ‘70s, Orthodox women covered their hair only for synagogue, when they donned hats worthy of a royal garden party.

It was during my first solo trip to Israel that the idea of head covering as a regular routine first occurred to me. I was a Barnard sophomore wavering between my yeshiva day-school upbringing and the liberal, humanist, and nonreligious philosophy favored by my professors and fellow students. I felt like the Matriarch Rebekah, when Esau and Jacob were pummeling each other in her belly. The headscarf wearers I met in Israel seemed to soar above this conflict. Maybe those headscarves were like tourniquets quashing their earthly demons and freeing their souls to fly to higher realms.

After another half-decade in New York, during which time I galloped through college and law school and got fed up with New York’s Jewish singles scene, I flew to Jerusalem. I was looking for faith and meaning and a good religious man who wanted to marry and have lots of children. A man like that would insist on bride who covered her hair. I was ready. After long days spent parsing Rashi’s commentaries at a women’s yeshiva, I stood at the mirror in my drab single-girl apartment looping the ends of a headscarf together like a tiara, dreaming of the day when my hair would go under wraps for good.

A week before my wedding, almost three years after I arrived in Israel, my friends threw me a tichel party, a bridal shower to which the guests bring headscarves. My favorite was a fuchsia and gold batik, which I wore to a black-tie sheva brochos post-wedding banquet hosted by my new in-laws. I felt radiant, swathed in my silky tichel’s consecrated glow.

Sadly, all too quickly my tichels sprang holes. My Manhattan fashionista impulses poked through—not in the form of an urge to uncover my hair; I was committed to the Torah requirement that a married woman reserve all of her sensual beauty for her husband. But while I was grateful for the safety sheath these requirements unfurled over my marriage, I wanted a style upgrade. This was the 1990s, and Princess Di came to my rescue by returning hats to fashion. My first was an oversized gray wool pillbox, roomy enough to cover my hair, and at the same graceful and elegant. At least that’s what I thought until I stepped outside and the neighborhood children made google eyes at me. To those kids, my hat looked like a Purim get-up.

That was far from the only problem. While tichels folded away in a drawer, hats needed special boxes and shelves. Worst of all, hats were notoriously fragile. One spring day, a gust of wind swept my favorite peach straw into the street, where a car ran it over.

Around this time, my best friend Joanne turned up to the newspaper office where we both worked, and she was wearing a wig. Until then, I’d never seen her wearing one. None of my friends wore them. Sheitels were for B’nei Brakers, born-and-bred Boro Parkers, not for artsy, earthy, slightly New Agey nouveau Haredim like Joanne and me.

Cut in a feathered Diana style (in the early ’90s everything was Diana-style), Joanne’s short blond wig—a $100 synthetic—softened her features and revealed a loveliness I’d never noticed when she wore a headscarf.

“Oh, you like it?” she asked me. “It’s from Tova the sheitel psychiatrist.”

Tova the what?

“She takes one look and knows which wig suits you best.”

Tova sounded like a Delphic oracle. I took down her number.

After many tries, I finally reached Tova. Her first opening was three months away. I grabbed it.

During that period, Joanne died. She wasn’t sick. She wasn’t hit by a truck or blown up by a terrorist. She got a terrible headache and then she was gone, leaving a husband and three children, the youngest of whom was a girl of 4. My appointment fell right after the shiva week. I canceled. For a time, I forgot about sheitels.

Then, one warm spring day about six months later, when I was highly pregnant and feeling like my body had been taken over by my stomach, I drifted into a downtown Jerusalem sheitel salon. The stylist handed me a catalog full of pictures of the same woman in hundreds of different styles, as if she were preparing to enter a witness protection program. I chose a dark brown pageboy.

After a half hour of sitting still while the stylist snipped and combed the wig that was affixed to my head with an elastic band, I was ready. I thought I looked good; maybe too good? Was I violating the spirit of the modesty laws? The last thing I wanted to be was a head-turner in a sheitel.

But at home, my brand new wig looked as if it was made of molten plastic. I was devastated. Had I been deceived by the salon’s lights? By my faulty eyesight?

“Take it to my girl,” said my sheitel-maven cousin Hedva. Hedva’s “girl,” who happened to be a grown woman, was booked solid.

“I’ll book you with Shula tomorrow. She’s just as good,” the salon receptionist said.

Against my better judgment, I took the appointment.

“The color removes the light from your face,” Shula said while looking at my new purchase, her face set in a frown.

She snipped and teased and combed, turning my light-deflecting pageboy into a light-deflecting pixie.

Back at home, my kids said the short sheitel turned me into an alte bubbe, an old grandma. I was barely 34. I returned the wig to its box and went back to hats and scarves.

On a visit to the United States, my pal Rivi booked me into her own sheitelmacher, Chani, the top stylist at the leading salon, in the sheitel capital of the world: Boro Park, Brooklyn.

“You don’t know what a big favor she is doing by squeezing you in,” Rivi told me with great seriousness.

After a five-hour wait, my turn to see Chani arrived. True to form, she picked out the perfect wig, a short frothy bob that struck the elusive balance between elegance and modesty. I floated out of the salon on a cloud of love for all the other sheitel wearers who crowded the Boro Park streets, all of us sisters under our wigs.

Back home in Jerusalem, I gave my new sheitel to my babysitter’s wayward niece, who claimed to be a beauty school graduate, for a wash. She blow-dried the curls to straw.

Since that time nearly 20 years ago, I’ve worn my way through a dozen or more wigs. I’m still searching for that perfect one.

On my current search I learned about a new innovation in the rapidly evolving world of sheitel technology: a hairpiece that converts a band fall (a wig with a cloth headband replacing the hair in front) into a full wig. Since I already have a band fall, the sheitelmacher suggested this. Priced at $520, as opposed to up to four times that price for a regular wig, it almost seemed like a steal. I ordered one over the telephone sight unseen, but on its Styrofoam wig head, it looked like the front of a Lhasa Apso pup.

On my head, the piece is an 18-year-old’s hair framing my 53-year-old face, like Dorian Grey in reverse. Do I like it? Right after the stylist had finished her work, I did, but once I got home, the combs holding the two halves together popped open, making me look me look like Marge Simpson.

So, I’m back where I started. And as I ponder my options—continue the search for something new, try to fix the damaged wig I already bought, stick it out with my old wig, or go back to scarves and hats—I know one thing: I’m still feeling bad about my sheitel.