Orthodox Jews in hairy dilemma on wigs

In all the years she has worn a sheitel, Chaya Epstein never doubted it was the proper way to hide her hair--until students at the Lubavitch Girls High School asked why she was still wearing her wig when other Orthodox Jewish women had taken theirs off.

The girls were responding to a vexing theological question that has rolled westward from the Holy Land through New York and on to Chicago's Orthodox community: Are sheitels made of human hair imported from India not kosher?

The consternation began when an influential Israeli rabbi ruled that the hair violated the biblical prohibition against idol worship because much of the product comes from a Hindu temple where worshipers donate their locks.

In Brooklyn, the pious set curbside bonfires of suspect sheitels, and there have been reports of wig burnings in Israel. The Chicago Rabbinical Council has called for calm even as local sheitel vendors report a rash of phone calls from customers anxious to know their wigs' provenance.

"Suddenly, everyone wants to go synthetic wigs," said Linda Keefe, proprietor of Linda's Head Quarters in Skokie, which sells human-hair wigs as well as artificial wigs and hats imported from Israel.

The crisis could lead to the greatest product recall in the history of Judaism, but it also touches on broader concerns, as it opens the sensitive issue of differences between faiths.

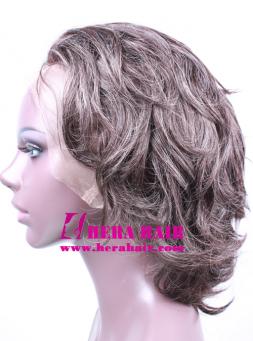

According to Orthodox teaching, because hair is erotically attractive a married woman should reserve its viewing for her husband's pleasure. The purity of sheitels having been called into question, some Orthodox women are taking the alternative of wearing a snood or a hat.

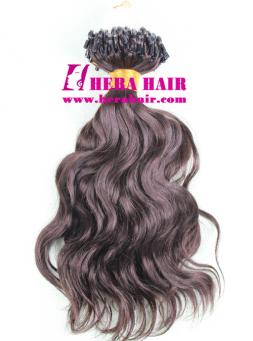

But in the Lubavitch branch of the Orthodox community, to which Epstein belongs, a human-hair wig is considered optimal, as it fits tightly over a woman's locks, completely covering them. It is not an inexpensive way to go: An up-market sheitel retails for $1,200 to $2,000.

When the controversy reached the North Side school where Epstein teaches, she considered exchanging her wig for one made of artificial hair. Then she recalled a bit of rabbinical reasoning known as a double doubt.

"The first doubt is that Indian hair might be impure, and the second is whether your sheitel contains any Indian hair," she said. "The product of a double doubt should be a wait-and-see attitude."

India is a leading supplier to the international hairpiece market, with much of the hair collected at the Tirupati temple in southern India. Besides going into sheitels, it is used to make wigs for those who have lost their own hair to disease.

Rabbi Shalom Elyashiv, a spiritual leader of Israel's Orthodox community, last month decided that Indian hair violated avoda zara, the prohibition against idol worship.

Further study needed

Amid the uproar that ensued, the Chicago Rabbinical Council has been trying to steer a middle course, according to its executive director, Rabbi Joseph Ozarowski. The group, which enrolls local Orthodox rabbis, has advised that sheitels known to be made from Indian hair should not be destroyed but set aside, pending further investigation of the religious implications of their origin.

"Most of us in Jewish community understand the Hindu religion includes various gods," said Ozarowski. "We are commanded to distance ourselves from anything that smacks of idolatry."

Indeed, the Jewish Press, a Brooklyn newspaper covering the Orthodox community, warned readers against inadvertently violating the ban even as they follow the controversy in its pages. The weekly noted that the Tirupati temple is dedicated to "an idol named Venkateswara" but reminded readers not to speak the name aloud.

Ozarowski said one way to resolve the issue would be to dispatch an observer to India to see exactly what takes place when hair is donated at the Tirupati temple. The problem is that Orthodox Judaism doesn't have one ultimate authority; instead, different sections of the community look to different rabbinical scholars for leadership. So it's unclear how widely any ruling would be accepted.

Bhima Reddy, a leader in Chicago's Hindu community, recently returned from India, where he found that newspapers were closely following the sheitel controversy. The country's human-hair industry is a multimillion-dollar enterprise, he said. It also has helped make the Tirupati temple a wealthy institution.

"People will make a vow, say, `If my father gets a promotion, I will go to the temple and donate my hair,'" Reddy explained.

He says he can't see why there should be such a fuss over the hair winding up in Jewish wigs.

"It doesn't make sense to me," said Reddy, a trustee of the Hindu Temple of Greater Chicago. "Once the hair is offered to the priests, it is a simple commercial transaction."

Possible way out of impasse

At least some rabbinical scholars think there might be a gem of an idea there--and a way out of the present impasse. The critical issue is whether the honoring of the Hindu god applies simply to the act of the hair's donation or to the hair itself.

"We have many questions," said Ozarowski. "Do they perform any kind of ritual before selling the hair to a sheitel maker?"

In the meantime, sheitel makers have been taking ads in Jewish newspapers saying their products are free of Indian hair. Other ads list brand names now unacceptable according to Elyashiv's pronouncement. Some wig merchants are touting their hairpieces as imported from China.

Master sheitel-maker Rachel Sullivan, proprietor of the Sheitel Clinic in Baltimore, said Indian hair is particularly in demand because of its dark color. Much of the hair sold by poor people to eke out a living comes from Russia, "where the range of hair color runs from blond to light brown," Sullivan said. "Most of my customers have dark brown hair."

Sullivan's solution to the dilemma is to carefully tint hair imported from Europe to match the color of a buyer's locks. She also avoids hair from China, even though it would seem ideal, colorwise.

"Just because a sheitel is advertised as being made in China," she said, "that's no guarantee it's not been made of hair the Chinese imported from India."

Orthodox issue only

Jonathan Sarna, author of "American Judaism: A History," said he thinks the sheitel controversy could widen already contentious divisions between the Orthodox and Conservative and Reform Jews, who don't require that women's hair be hidden and might see themselves as being dragged into a religious battle for which they didn't sign up.

"Many Conservative and Reform Jews have long felt they don't understand the fervently Orthodox," Sarna said. "They might say: `While the whole world is globalizing, the Orthodox are isolating themselves from the modern idea that all religions are viable and revered.'"

Yet Chaya Epstein doesn't think there is anything outmoded about sheitels and the rules and regulations applying to them. To her, head coverings are both traditional and as up-to-date as the feminist movement.

When women entered the corporate world, they started dressing more conservatively, Epstein argues. She attributes that change to a desire to be recognized as something more than a pretty face. A similar impulse inspires the Orthodox use of a sheitel, she said.

"By de-emphasizing the physical," Epstein said, "we emphasize the whole dignity of a woman, her inward life instead of her external appearance."